By Carmen Heredia Rodriguez, Elizabeth Lucas, and Orion Donovan-Smith | Kaiser Health News

In his 40 years of working with people struggling with addiction, David Crowe has seen various drugs fade in and out of popularity in Pennsylvania’s Crawford County.

Methamphetamine use and distribution is a major challenge for the rural area, said Crowe, the executive director of Crawford County Drug and Alcohol Executive Commission. But opioid-related overdoses have killed at least 83 people in the county since 2015, he said.

Crowe said his organization has received just over $327,300 from key federal grants designed to curb the opioid epidemic. While the money was a godsend for the county — south of Lake Erie on the Ohio state line — he said, methamphetamine is still a major problem.

But he can’t use the federal opioid grants to treat meth addiction.

“Now I’m looking for something different,” he said. “I don’t need more opiate money. I need money that will not be used exclusively for opioids.”

The federal government has doled out at least $2.4 billion in state grants since 2017 to address the opioid epidemic, which killed 47,600 people in the U.S.that year alone. But state officials noted that drug abuse problems seldom involve only one substance. And while local officials are grateful for the funding, the grants can be spent only on creating solutions to combat opioids, such as prescription OxyContin, heroin and fentanyl.

According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 11 states have reported that opioids were involved in fewer than half of their total drug overdose deaths in 2017, including California, Pennsylvania and Texas.

The money is also guaranteed for only a few years, which throws the sustainability of the states’ efforts into question. Drug policy experts said the money may not be adequate to improve the mental health care system. And more focus is needed on answering the underlying question of why so many Americans struggle with drug addiction, they said.

“Even just the moniker, like ‘the opioid epidemic,’ out of the gate, is problematic and incorrect,” said Leo Beletsky, an associate professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University in Boston. “This was never just about opioids.”

Drug Deaths Are ‘Not Just About Opioids’

States have received $2.4 billion in federal funds since 2017 to battle the opioid epidemic, which killed 47,600 people in the U.S. that year alone. The money has provided needed services for many areas, but states note that abuse problems seldom involve only one drug. According to federal data, 11 states have reported that opioids were related to fewer than half of their total drug overdose deaths in 2017. The rates in this chart are calculated per 100,000 residents and the percentage of opioid deaths is calculated using raw death numbers.

| State | Drug overdose death rate | Opioid death rate | Percentage of drug overdose deaths caused by opioids | Total funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 17 | 9 | 51% | $36,854,321 |

| Alaska | 20 | 14 | 69% | $10,130,347 |

| Arizona | 22 | 13 | 61% | $55,192,915 |

| Arkansas | 15 | 6 | 42% | $15,673,424 |

| California | 12 | 6 | 45% | $195,798,273 |

| Colorado | 18 | 10 | 57% | $38,711,085 |

| Connecticut | 30 | 27 | 89% | $27,939,737 |

| Delaware | 35 | 26 | 74% | $23,168,955 |

| District of Columbia | 45 | 35 | 79% | $36,154,971 |

| Florida | 24 | 16 | 64% | $130,487,333 |

| Georgia | 15 | 10 | 66% | $53,825,421 |

| Hawaii | 14 | 4 | 26% | $10,143,778 |

| Idaho | 14 | 6 | 44% | $10,257,193 |

| Illinois | 22 | 17 | 79% | $76,778,990 |

| Indiana | 28 | 18 | 63% | $49,472,057 |

| Iowa | 11 | 7 | 60% | $12,180,388 |

| Kansas | 11 | 5 | 43% | $12,388,773 |

| Kentucky | 35 | 26 | 74% | $68,965,468 |

| Louisiana | 24 | 9 | 37% | $34,204,076 |

| Maine | 32 | 27 | 85% | $10,809,555 |

| Maryland | 37 | 33 | 88% | $70,557,464 |

| Massachusetts | 32 | 28 | 88% | $78,427,729 |

| Michigan | 27 | 20 | 75% | $75,231,441 |

| Minnesota | 13 | 8 | 58% | $24,260,217 |

| Mississippi | 12 | 6 | 52% | $18,790,086 |

| Missouri | 22 | 16 | 70% | $47,981,862 |

| Montana | 11 | 4 | 32% | $10,134,223 |

| Nebraska | 8 | 3 | 39% | $9,030,457 |

| Nevada | 23 | 14 | 61% | $22,314,877 |

| New Hampshire | 35 | 32 | 91% | $41,569,261 |

| New Jersey | 30 | 22 | 73% | $58,814,746 |

| New Mexico | 24 | 16 | 67% | $17,662,772 |

| New York | 20 | 16 | 82% | $106,579,365 |

| North Carolina | 24 | 19 | 81% | $66,230,155 |

| North Dakota | 9 | 5 | 51% | $10,118,505 |

| Ohio | 44 | 37 | 84% | $137,034,294 |

| Oklahoma | 20 | 10 | 50% | $26,210,237 |

| Oregon | 13 | 8 | 65% | $25,110,201 |

| Pennsylvania | 42 | 20 | 47% | $138,138,650 |

| Rhode Island | 30 | 26 | 87% | $23,503,736 |

| South Carolina | 20 | 15 | 74% | $34,846,327 |

| South Dakota | 8 | 4 | 48% | $10,117,439 |

| Tennessee | 26 | 19 | 71% | $55,852,845 |

| Texas | 11 | 5 | 49% | $125,085,392 |

| Utah | 21 | 15 | 70% | $23,187,948 |

| Vermont | 22 | 18 | 85% | $10,119,804 |

| Virginia | 18 | 15 | 82% | $43,587,467 |

| Washington | 16 | 10 | 63% | $56,414,760 |

| West Virginia | 54 | 46 | 86% | $54,754,439 |

| Wisconsin | 20 | 16 | 79% | $33,506,421 |

| Wyoming | 12 | 8 | 68% | $10,111,282 |

KHN analyzed federal funding from USASpending.gov by totaling all grants given to state governments under the Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (CFDA) No. 93.788, which includes both State Targeted Response and State Opioid Response grants. The first grants were awarded in May 2017 and the data is current as of May 10, 2019. All drug overdose deaths and opioid-related drug overdose deaths for 2017 were downloaded at the state level from CDC Wonder. Using an outline from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), KHN totaled all drug overdose deaths using the underlying cause-of-death ICD-10 codes X40-X44, X60-X64, X85 and Y10-Y14. KHN further totaled opioid-related drug overdose deaths identifying drug overdose deaths with multiple cause-of-death ICD-10 codes T40.0, T40.1, T40.2, T40.3, T40.4 and T40.6.

States received federal funds for opioids primarily through two grants: State Targeted Response and State Opioid Response. The first grant, authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act, totaled $1 billion. The second pot of money, $1.4 billion — approved as part of last year’s omnibus spending bill — sets aside a portion of the funding for states with the most drug poisoning deaths.

For states like Ohio and Pennsylvania, the need was great. Nearly 4,300 and 2,550 residents, respectively, died from opioid-related overdoses in 2017. State officials say the money enabled them to invest significantly in programs like training medical providers on addiction, more access points to treatment and interventions for special populations, like pregnant women. Ohio was awarded $137 million in grants; Pennsylvania, $138.1 million.

The grants also stipulate a minimum amount of money for every state, so even areas with reportedly low opioid-related overdose death rates now have considerable funds to combat the crisis. Arkansas, for example, reported 188 opioid-related deaths in 2017 and received $15.7 million from the federal government.

While 2,199 people in California died from opioid-related causes in 2017, its opioid death rate was one of the 10 lowest in the country. The Golden State received $195.8 million in funding, more than any other state.

“This funding is dedicated to opioids,” said Marlies Perez, a division chief at the California Department of Health Care Services, “but we’re not blindly just building a system dedicated just to opioids.”

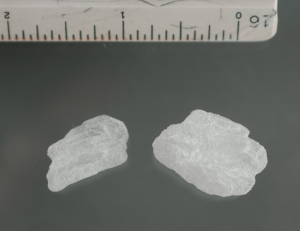

Mounting evidence points to a worrisome rise in methamphetamine use nationally. The presence of cheap, purer forms of meth in the drug market coupled with a decline in opioid availability has fueled the stimulant’s popularity. The number of drug overdose deaths involving the meth tripledfrom 2011 to 2016, the CDC reported. Hospitalizations involving amphetamines — the class of stimulants that includes methamphetamine — are spiking. And it is harder to address. Treatment options for this addiction are narrower than the array available for opioids. In light of the increase in deaths related to other substances, are these grants the best way to fund states’ response to opioids?

Bertha Madras, a professor of psychobiology at Harvard Medical School and a former member of the federal Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission, said the federal government has responded well by tailoring the response to opioids because those drugs continue to kill tens of thousands of Americans per year. But, she said, as more people living with addiction are identified and other drugs rise in popularity, the nation’s focus will need to change.

Beletsky emphasized that the grants are insufficient to support fixes to the mental health care system, which must respond to patients living with an addiction of any kind.

People addicted to a particular substance typically use other drugs as well. Controlling addiction throughout a person’s life can be akin to “whack-a-mole,” said Dr. Paul Earley, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, because they may stop using one substance only to abuse another. But specific addictions may also require specific treatments that cannot be addressed with tools molded for opioids, and the appropriate treatment may not be as available.

“I think we have to really begin to self-examine why this country has so much substance use to begin with,” Madras said.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.