In January, I hosted an event that highlighted how Pennsylvania’s system of fragmented local governments hinders public oversight. The level of interest in the topic and the number of questions from attendees overwhelmed me, delighted me — and it gave me an idea. What if I answered your questions about the commonwealth’s more than 2,500 municipalities on a regular basis?

By Min Xian | Spotlight PA

Have you ever wondered how your municipality makes a decision? Perhaps you see a renovation project going on and want to understand the need for the makeover or its costs. The meeting minutes of a planning commission or a contract with builders, among other kinds of public records, might answer your questions.

Where should you look? This information may not be available online, but you might be able to obtain it by asking for it.

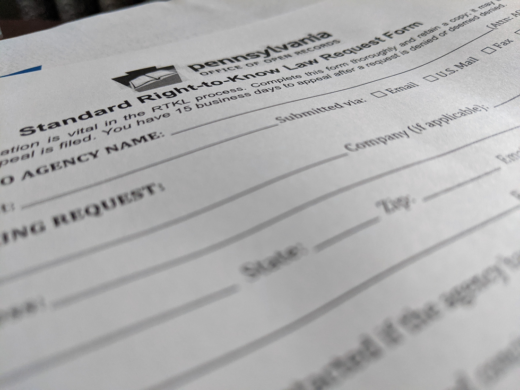

Pennsylvania’s Right-to-Know Law grants public access to all government records unless their disclosure is barred due to specific exceptions, such as a protective order or doctor-patient privilege.

Understanding the basics of the law can help you follow the decisions of state and municipal governments. Here’s what you should know:

Assume a record is public

Under the Right-to-Know Law, all records are presumed to be public records, and the burden is on government agencies to establish why they might not be available.

Commonwealth agencies, including the offices of the governor and attorney general; local agencies like boroughs, townships, school boards, and authorities; and legislative bodies are covered by the law. Notably, Pennsylvania courts and other judicial agencies only need to provide financial records under the law.

What are public records?

The open records law defines a broad range of information as a record, as long as it “documents a transaction or activity of an agency and that is created, received or retained pursuant to law or in connection with a transaction, business or activity of the agency.” Basically, if a record involves a government agency or public funds, the public deserves access to it.

Public meeting minutes, emails relating to an agency’s business, contracts, and payrolls involving public funds are some examples of public records.

Making a request

Any legal resident of the United States can submit a request under the law. Requesters do not need to explain the reasons why they seek the information, but should keep the ask limited in subject matter, specific in scope, and within a certain time frame.

Doing some research before submitting a request can be worthwhile. The information you seek could already be publicly accessible. (If that’s the case, an agency may tell you just that.)

Pennsylvania’s Office of Open Records maintains a list of all open records officers in the commonwealth. Before making a request, consider getting in touch with an officer to find out how their agency keeps records and what wording would identify what you’re looking for. Check out the Right-to-Know case law index published by the Office of Open Records to find court interpretations of how the law should work.

Agencies have to respond to your request within five business days of submission. They can grant the request, deny it, or invoke a 30-day extension to respond.

Keeping track of response time is essential, especially if an appeal becomes necessary. Spotlight PA’s Ed Mahon recently explained five key elements of the appeal process.

Limitations of the law

Personal information such as Social Security numbers, privileged information such as that between an attorney and a client, and law enforcement information like ongoing criminal investigations are among the records shielded by the law.

Very rarely, requesters’ right to demand public records through the law might be limited.

David Rosner sued Buckingham Township in 2020, claiming the Bucks County municipality charged him excessive and impermissible fees as he sought approval of a stormwater management plan and building permit. He settled the lawsuit in January, and the township agreed to grant him both approvals and make other concessions.

But Rosner said Buckingham Township also demanded that he drop several Right-to-Know requests and appeals. (He had filed several requests while the legal process played out.) According to the settlement, the township required that he not submit new requests for 42 months, “unless it is for primarily a bona fide, good faith salutary reason” and “does not result in the harassment, annoyance, or unreasonable burden to [Buckingham Township].”

Rosner accepted the terms but told Spotlight PA he was frustrated that the township leveraged his rights to public information “in a legal negotiation that had nothing to do with [the Right-to-Know Law].”

Buckingham Township Manager Dana Cozza disagreed and told Spotlight PA the intent of the settlement was to “settle a multitude of lawsuits, including several appeals of Right to Know Requests.”

The condition to limit Rosner’s open records request was the result of a negotiation Rosner was a part of, Cozza added. “It is not onerous to have Mr. Rosner exercise the same good faith in making Right to Know requests, that the Township must exercise in responding to them.”

While it’s crucial to acknowledge that Rosner agreed to the condition voluntarily — and was not forced by the government — this scenario “is something to be cautious about,” said Melissa Melewsky, media law counsel for the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association, which Spotlight PA is a part of.

“If agencies begin to prohibit RTKL requests as a negotiating tool … it could discourage access for others and lead to unintended negative consequences. Obviously, that would conflict with the letter and intent of the [law],” Melewsky said.

SUPPORT THIS JOURNALISM and help us reinvigorate local news in north-central Pennsylvania at spotlightpa.org/statecollege. Spotlight PA is funded by foundationsand readers like you who are committed to accountability and public-service journalism that gets results.